[Begin Tu Video]

[Slide #1- A Modern Framework for Understanding Endometriosis- 00:09:32 ASRM-Part 2_10.19.15.MP4]

A Modern Framework for Understanding Endometriosis-Associated Pelvic Pain Disorders - Dr. Frank Tu. MD

I would like to introduce Dr. Frank Tu. Dr. Frank Tu is a clinical associate professor at the University of Chicago. He is also the director of the NorthShore University HealthSystem division of Gynecological Pain and Minimally Invasive Surgery. [Start at 00:11:32 ASRM-Part 2_10.19.15.MP4]

So uh, Bill did go over objectives, and for my part, uh, we’re going to quickly go over understanding how important central pain processing is in understanding how some women experience endometriosis different from others. Then, we’re going to incorporate a holistic longitudinal view of pain sensitivity in managing endometriosis, which Bill was kind enough to go and start with.

We’ll start right off the bat and say let’s extend from what Bill finished up with talking about hormonal influences on the periphery and introduce the concept of central pain.

I just got back from Society for Neuroscience, this is in Chicago concomitantly right now, and there’s no one really talking about peripheral lesions and pain, because, as neuroscientists, they talk about the entire nervous system.

This is a classic construct that everyone here needs to understand as a scientist or as a clinician. This idea that, while as a pelvic surgeon, I’m used to thinking about everything being either a nociceptive or perhaps an early and inflammatory pain state. Then in the broader pain world, they have long moved past these terms of thinking that surgery to remove inflamed tissue takes care of pain disorders. It’s far more complex. Pain is a $50 billion industry that affects something on order of like one-sixth of all Americans. There’re lots of different way to study

[end ASRM-Part 2_10.19.15.MP4]

[begin ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

this, besides just studying it in the pelvis or looking at aberrant, rogue endometrial tissue.

When you step away and stop thinking as a gynecologist, you learn a lot it turns out.

Clifford Woolf has done an enormous amount of work on the construct of neuropathic pain, and he says that there are ways of viewing things that are very simple. The standard view of like when you stick a tack into your finger gently enough to depress the tissue, but not enough to actually break the skin, it’s what is called nociceptive pain.

It’s a physiologic pain that serves a protective function which is to stop putting the sharp, painful thing into your finger. It’s transient, and it’s not pathologic. It’s doing a good thing, which is to steer you away from a threat. The term threat will come again several times in my talk, because I think it’s a really important construct in understanding clinical pain conditions.

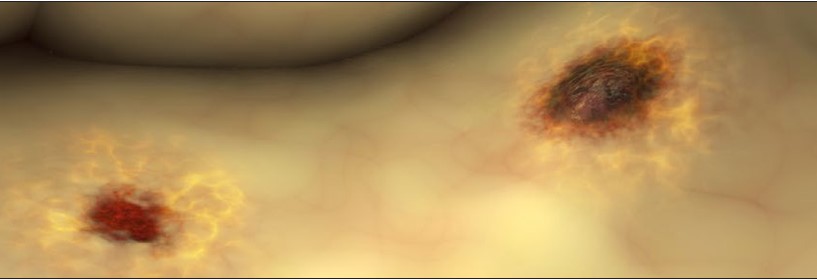

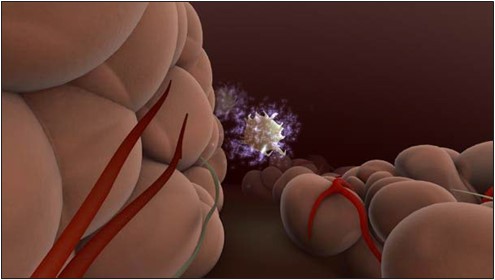

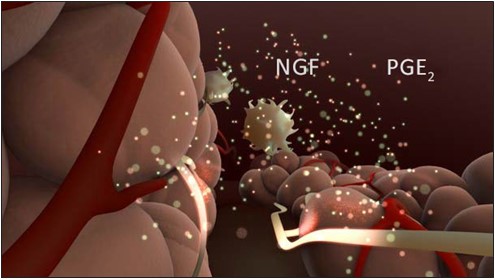

[Slide #2 – Nociceptive vs inflammatory pain – 00:00:45 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

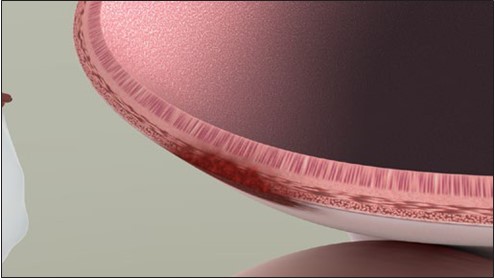

The actual issue that becomes a problem when we are clinically facing pain is at the onset, inflammatory pain. As you can see in this little cartoon here, this is when you get the inflammation that accompanies actual tissue damage, which activates correctly a nociceptor and results in things that we see in clinical practice: spontaneous pain, at least until the process is reversed, but also pain hypersensitivity, which Bill has talked about in a couple of his slides as well.

There are two aspects of that that we will see in clinical practice: allodynia, something hurts that shouldn’t, and hyperalgesia, something hurts a lot more than it ought to. These are the people that say I can’t even tolerate the feeling of my clothing on my abdomen. These are very important terms. Inflammatory pain typically goes away, you know That’s the goal of the surgeon is to remove the inflammatory pain of endometriosis. The problem is that there are just as many issues arising out of neuropathic and central pain states, which for many clinicians is not something that we have any tool or blood test to diagnose.

[Slide #3 – Neuropathic vs central pain – 00:01:50 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

But in neuropathic pain, there is actually an aberrant process in the peripheral nervous system, which as a result, results in when you stimulate the peripheral afferent, there’s a far greater activation of the nervous system, going up and activating the brain and saying there’s a threat locally. When you have a neuropathic condition, this is not subserving the goal of the nervous system, which is to avoid threat. It is not protective. This is the first of many steps towards the pathologic pain that many patients with “chronic pain” experience.

There are other variants of it where, even with no history of a seeming initial inflammatory insult, you can actually end up with spontaneous functional pain, or what we call true central pain. As you can see here, nothing has happened to the actual distal peripheral mechanisms or even the spinal cord, but there’s something going on in the higher-order centers. This is something that Bill has eluded to when he talked about the epigenetics of endometriosis, and it’s something that’s very interesting. But, this is a clinical pearl. Take away and understand what do we have here? Do we have a patient that has a central process or is it entirely an inflammatory process as we’re trying to decide who goes to the operating room or who gets prolonged treatment with hormonal therapy.

[Slide #4 – Central neuronal sensitization plays key role in chronic pain- 00:03:03 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

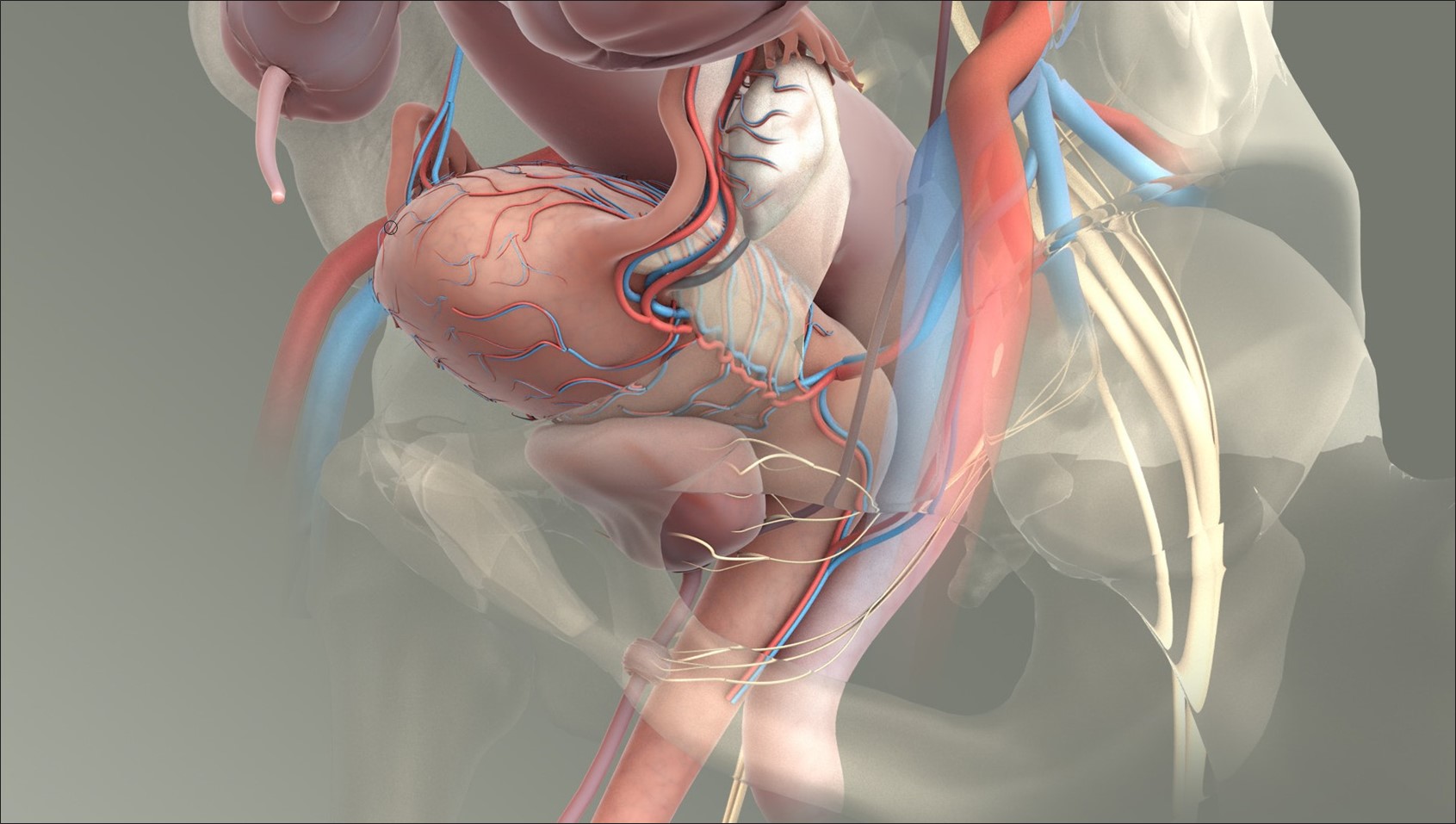

Let’s look real quickly at a couple of slides on how the higher-order parts of the nervous system actually process pain. We use them term central sensitization to refer to the fact that neurons normally involved in the threat characterization in trying to make a healthy organism avoid something that might injure it are unfortunately being hijacked into doing things inappropriately. This can occur both at the spinal level in classically the dorsal horn, which is where a lot of the work has been done in animals, but is also undoubtedly involving supraspinal levels involving the brain stem and the cortex as well.

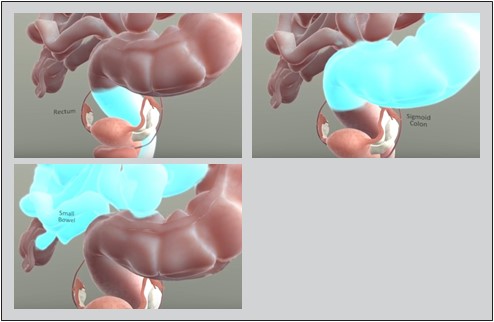

A classic example is, of course, irritable bowel syndrome, where you see persistent colon hypersensitivity in the absence of any abnormal findings on colonoscopy. Classic studies done by a number of investigators in the GI field have indicated that if you look at spinal visceral receptive neurons in animal models that have been exposed to a priming insult in their neonatal period of development, that long after any visible signs are there, you see increased firing rates in these neurons. You see that when you do an irritating balloon distention of the colon, that there’s a lower threshold needed to activate these neurons, and there’s an exaggerated response in terms of the amount of exhibited pain behavior as well.

So,central sensitization is one of these key mechanisms that we do see in these pain patients that has been shown in animal models consistently.

[Slide #5 – Pain-Inhibitory and -Facilitatory Mechanisms in Dorsal Horn Influence Development of Chronic Pain – 00:04:24 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

It’s actually really quite complicated, because at the level of the dorsal horn, your classic spinothalamic neuron that’s getting input from say either a C-fiber from the viscera or perhaps an A-beta mechanoreceptor is already being influenced by other interneurons; some playing a positive role; some playing a negative role in terms of ultimately deciding does a threat signal go up to the brain or not. These are in turn influenced by these peripheral afferents as well.

This is an extremely challenging issue then to try to explain to a patient, to try to say, we know there are these anatomical nerves. We have no idea what’s going on once they disappear into your spine. How many of them are aggregating together and saying let’s get a go signal versus a no-go signal for actually should we say there’s a threat in the periphery.

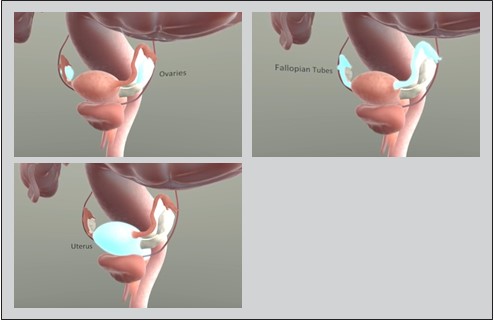

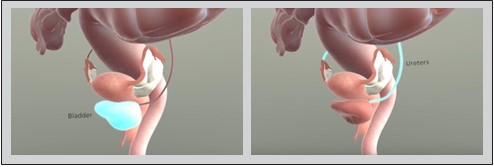

This hypersensitivity has been studied at a number of related visceral pain conditions, particularly by work in both the bladder and bowel realm.

[Slide #6 - Hypersensitivity Is a Hallmark of Visceral Pain Disorders- 00:05:18 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

In this work here by Tim Ness at the University of Alabama, who is actually one of my medical school professors, he shows some very simple and elegant studies where you simply fill up the bladder backwards, like a standard cystometry. You can see that in healthy subjects, as you increase the total amount of volume that sure, the amount of discomfort and unpleasantness goes up, but in patients with existing chronic bladder pain, they exhibit visceral hypersensitivity like the animals, higher levels of pain report and unpleasantness, and they can’t tolerate nearly as much. As you can see, their total cystometric capacity is markedly lower in contrast to healthy subjects, and the amount of distending pressure they may put in is also lower in the IC subjects. So visceral hypersensitivity, again to pair it to Bill’s earlier slides, is one of the hallmarks of chronic pain disorders and a very important thing to look for in patients.

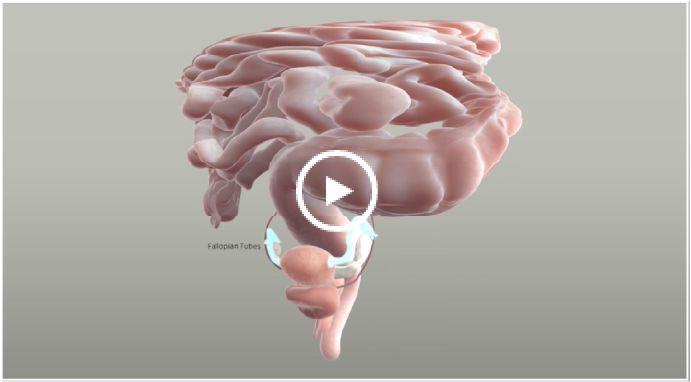

So let’s look at sort of what the underlying neuroarchitecture is. Why do we think that these patients don’t simply respond to conventional surgery all the time or to hormonal therapy? And again, if you go back and step away from any of our hats as pelvic surgeons or gynecologists, there’s been plenty of work done by these neuroscientists. The big questions in pain, in idiopathic pain disorders is, what is the underlying spark?

[Slide #7 - The Genesis of Pain in Endometriosis Is Complex – 00:06:31 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

Is it someone’s underlying genetics? Did they have an early life sensitizing event, which we’ll talk about it a little bit, or did they have something happen maybe later on in life? Either way, the model is that based on a person’s life experience in trajectory, they end up with central sensitization and this exhibits as things like autonomic dysfunction. You get neuroendocrine disturbances, like some of the associated symptoms, like PMS you might see in endometriosis patients. You get the exhibited classic objective signs of peripheral or visceral hypersensitivity. Even if you do biopsies, you can see things like an excess of influx of immune cells.

Outside of the endometriosis world, there’s a very complex degree of understanding that shows that all the things that we associate with endometriosis are not entirely uncommon in general in chronic pain states.

[restart at00:08:40 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

So, we have to be mindful of understanding what could these potential early events be, because in animal models this is a surefire way to fire up the nervous system and keep it abnormal into adulthood.

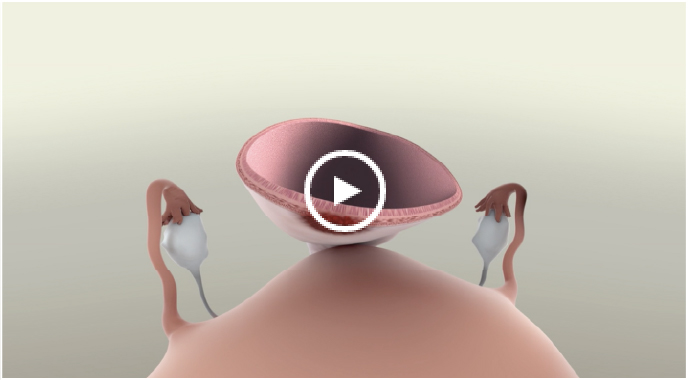

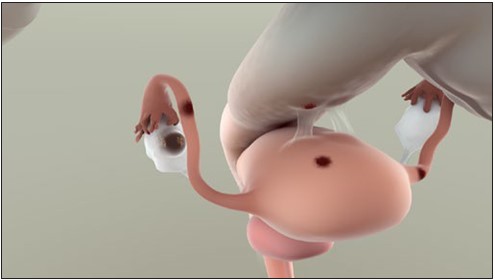

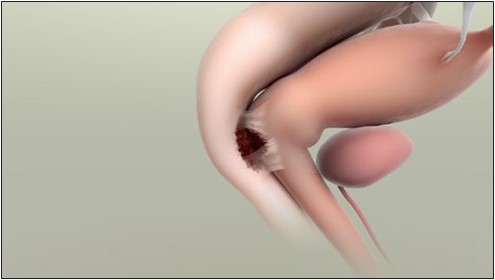

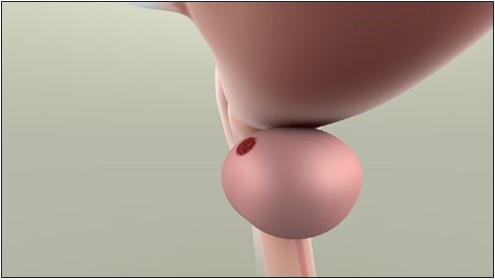

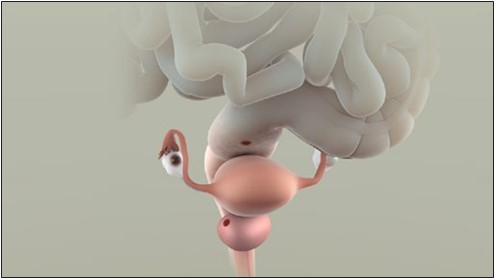

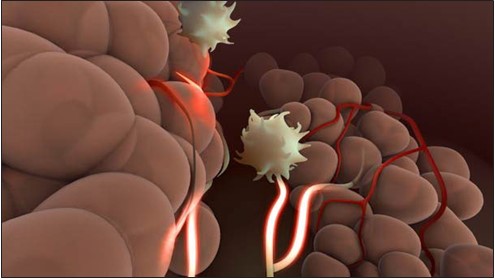

It’s not surprising that you might ask, well, what about in endometriosis? Is there some sort of early event there? Well, one possibility that has been classically described by Karen Berkley and others is to, of course, create endometriosis in an animal. You take uterine tissue and stick it somewhere it shouldn’t be.

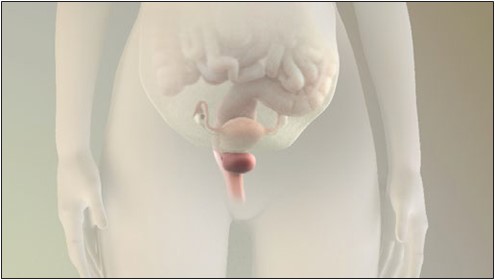

[Slide #8 – rat model mimics growth/development of surgically transplanted endometrial tissue –00:09:08 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

So, this slide that I borrowed from Karen from a talk she gave years ago is simply describing the classic studies that I suppose everyone here knows about where you autotransplant uterine tissue off onto the mesentery, and these nice little autotransplants grow in and get a blood supply, and their classic control thing is to take some fat and stick it in the same spot. In these animal models, their cysts will disappear if you take their ovaries out, so they’re hormonally sensitive, and they will reappear when you give them exogenous estrogen. They actually are subfertile as well.

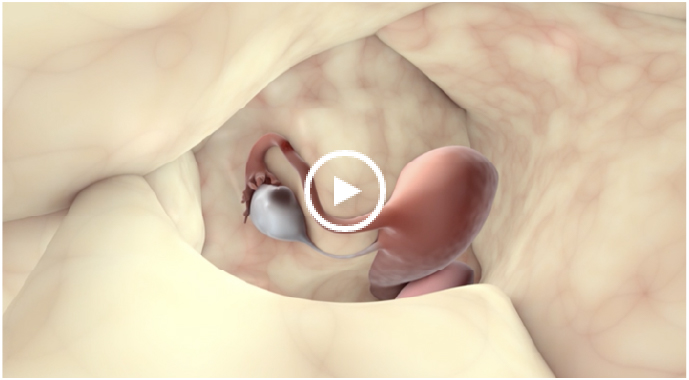

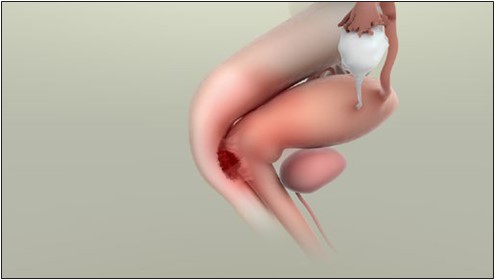

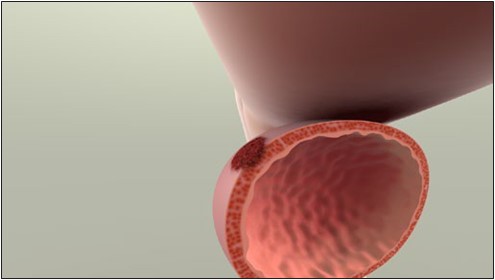

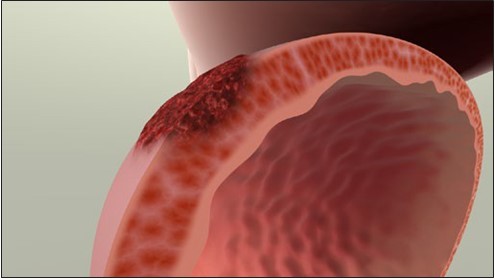

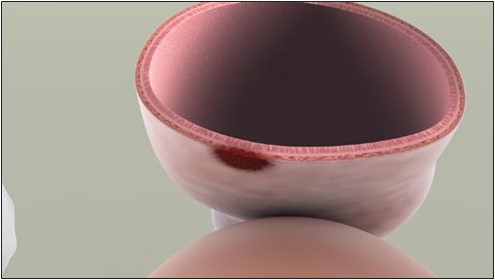

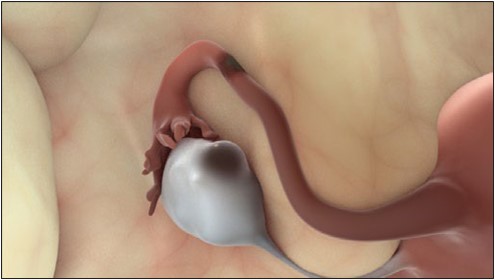

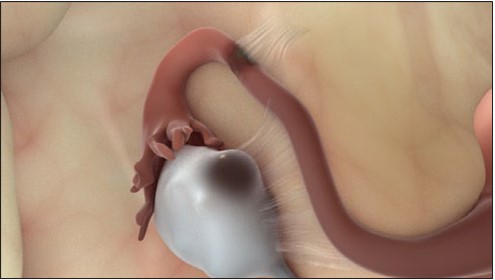

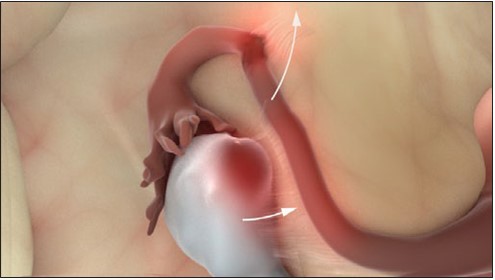

[Slide #9 - Endometriosis Induces Vaginal Hyperalgesia – 00:09:37 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

If you look at that classic model, you can see that after you induce this model in these rats and then sit around for a bit, that when you start doing vaginal distention, you get an increase in the irritability and attempt of the animal to escape from this unpleasant sensation as you increase the distention in the pretreatment thing, but once as you actually start provoking them by having an existing endometriosis implant in place, there’s an exaggerated escape response, indicating that you can do this sort of perturbation in animals as well and replicate the human endometriosis model.

Taking that data, we start to look at one of the earliest sort of pain markers or potentially pain-inciting events you can see in women, which is of course painful periods or dysmenorrhea. We were motivated by this by work that Krina Zondervan had done very elegantly almost 15 years ago in the United Kingdom.

[Slide #10 – Dysmenorrhea is a risk factor for chronic pelvic pain – 00:10:34 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

She did a large postal survey of English women and asked them about rates of dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea and also chronic pelvic pain. It was a very large study and very well designed. Krina is an epidemiologist of the first order doing a lot of genetics of endometriosis now.

A couple of things came out of this. One is that there’s a lot of women with painful periods, so this is by itself not a great screening tool, because that will be most people walking around on the street. But, what’s interesting is that of women with chronic pelvic pain, 80% of them report a history of dysmenorrhea, indicating that if you crack dysmenorrhea, you might be able to crack a large number of the cases of CPP that I show right here in this overlapping box. But, that’s too simplistic, right? Because there’s not great specificity. If you just look at this, 32% of the women with dysmenorrhea would fall into this category. We have so many people that are obviously in the outside box that are not afflicted that this is not a sufficient public health strategy to make any sort of recommendations on.

What we found in subsequent studies—Allyson Westling was the first author. She’s now a medical student up in the northeast, but in her undergraduate work that she did with us, she collected data on about 1,000 women on a panel company survey and said, ”tell us about your menstrual pain, and then tell us about all sorts of other pain you might have in the viscera.”

[Slide #11 - Dysmenorrhea Is Associated With Severe Pelvic Pain – 00:11:53 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

We found that if you’re a person in the community, you have a thirteen-fold higher likelihood of having severe pelvic pain on spontaneous report if you also had significant menstrual pain. What’s even more interesting is that when you control for anxiety or depression, this is actually still a very significant robust association, indicating that dysmenorrhea is potentially an area to spend some time looking at.

In fact, in works that subsequently did on my career development award, we started looking further and saying let’s see what happens with dysmenorrhea when you start to provoke women in a nice, gentle way that they wouldn’t mind doing.

[Slide #12 - Dysmenorrhea Is Related to Dynamic Bladder Pain – 00:12:31 ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

The easiest way to do that, we found, was to basically have them drink a bunch of water. Like all of you guys have been doing hopefully and staying well-hydrated. Then waiting until they got basically into a state of essentially diuresis induces cystometry.

What we have here

[end of ASRM-Part 3 10.19.15.MP4]

[beginning of ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

on the x-axis is the relative quartile of how much you say your menstrual pain was in this group of young, college-aged women basically. This is an assay for how much bladder pain you have at first sensation, first urge, or maximum tolerance to bladder distention. In this paper that was published in clinical journal of pain in 2013, you can see that there are dramatic differences in the worst quartile of dysmenorrhea sufferers compared to those who report much milder pain. This was really the first time that anyone actually experimentally identified that bladder pain in people who don’t report bladder symptoms is present in women with dysmenorrhea, but it suggested these people who are walking around just saying, boy I have a miserable few days a month, have already had their nervous system hijacked for some very nefarious things by unfortunately an ill-designed system in this case.

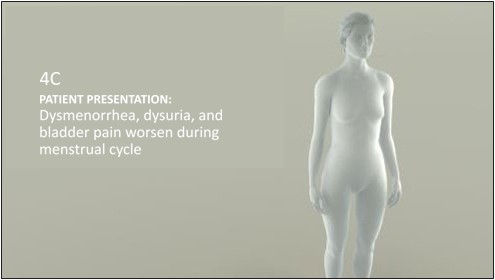

[Slide #13 – Potential therapeutic implications for endometriosis – 00:00:50 ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

And so, this is sort of a woe is me type of a picture, except for the fact that meanwhile, a colleague of ours in Italy, Maria Adele Giamberardino, an internist who’s been studying kidney stones for a long time, had already shown in a prospective study that was backing up a retrospective study,

that if you had the unfortunate bad situation of having both kidney stones and having painful periods, if you treat the actual painful periods with birth control pills, your kidney stone pain is not nearly as bad subsequently, which indicates that there’s some significant viscerovisceral interaction. This very sort of like provocative statement she made 15 years ago was that persistent afferent input to the spinal cord sustains altered central processing. This is what then leads to the clinical hyperalgesia, pain, and allodynia. So, 15 years ago she was in essence telling us go do a preventative study, see if you can knock out the persistent afferent input. Now, the question is where is that coming from? Is it coming from early endometriosis? Is it coming just from having the bad luck to have been born with a painful uterus? We really don’t know right now.

In my closing slides here—I’m a clinician like Bill, and I like to send people home with stuff they can actually think about and hopefully use in the clinic. Holistic therapies that can be employed by any of us here are relatively abundant.

[Slide #14 – Breaking the pain cycle with holistic therapies – 00:02:19 ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

There’s a lot of literature on cognitive behavioral therapy, and I’m going to talk about specifically one that is actually an offshoot called explained pain, that’s been very exciting for some of our patients. There’s, of course, physical therapy because sometimes the occult afferent driver is actually in the mechanical or musculoskeletal elements. Certainly, some of our patients respond to acupuncture or dietary changes, and these are admittedly very, very unproven but generally quite safe. There have actually been some RCTs using both garlic extract and melatonin published in just the last couple of years, and I would encourage people to look at those. Because they’re not in traditional OB/GYN journals, we don’t tend to look at that data, but people are interested in RCTs in endometriosis pain. The melatonin study was actually a positive result. It did work for endometriosis, surprisingly.

I’m going to talk about explained pain in the remaining couple of minutes.

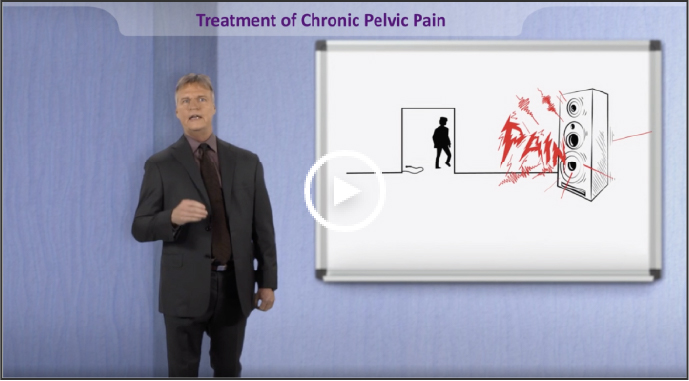

[Slide #15 – Pain is fundamentally dependent on meaning – 00:03:05 ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

One thing that I’ve been taught by not going to GYN pain meetings only is that there’s a lot people thinking about what is means to have pain, instead of just saying, oh, it’s my endometriosis acting up this month. People say, well, pain is really at the end of the day about threat, and pain is fundamentally dependent on meaning.

So, not all pain that we experience as humans has anything to do with something growing or inflamed inside of us. It’s not necessarily a marker of tissue damage or disease. Many people now say it is the sort of perceived need that is key. It is the threat of body tissue damage, whether it happens or not. They call this explained pain.

[Slide #16 – “Explain Pain” explained – 00:03:37 ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

Explained pain really says that perhaps to help some people out, if we can change the valence of their sensory experience, the threat value, that they may actually be able to shift their actual brain representation. This is not some hypnosis or some sort of psycho-babble. This is that literally the actual neural activity can change because of the contextual influence that our human cortices can play on our inputs coming from the periphery.

[Slide #17 – Preliminary data to support EP – 00:04:07 ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

A great example is this. Do people all recognize this classic picture of the immolating monk? This is from the Vietnam War, of course, probably I’m guessing in the early ‘50s in Saigon. So, it’s important to note that these monk immolations, when they happen, don’t seem to be accompanied by people screaming as they’re burning themselves to death. There are plenty of other less horrifying examples of this. The point is that whether it’s in religious experiences or other sort of significantly contextually driven experiences, not all highly nociceptive activating events cause pain. In fact, in a trial where they actually did this explained pain thing and tried to change the context in people with fibromyalgia, they were actually able to show that one of the key mechanisms underlying fibromyalgia, which is abnormal descending blocking of pain, improved just with the explained pain education.

Explained pain is a little bit more than just a CBT, and I would encourage you guys to read Lorimer Moseley’s work if you have an interest in this.

[Slide #18 – EP vs Conventional Understanding of Pain – 00:05:02 ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

Explained pain at its heart is not saying that you’ve got to just suck up and move more; it’s got to tell you that sometimes the information you’re getting is about threat, and it’s not about damage, and that your spinal cord isn’t necessarily giving you more pain messages, it’s giving you more danger messages. That’s a very freeing bit of information to tell patients. You’re danger and threat systems may be off, but sure has heck fire, you’re getting information from your body. No one’s lying here. It’s like, what does this mean? I think that the use of metaphors like the immolating monk are very powerful, very powerful metaphors to share with patients that really can help them start to help themselves in ways that we may be, at the current moment, sort of limited in our ability to do.

[Slide #19 – Summary – 00:05:44 ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4]

So in summary, I think it’s really important to think about a longitudinal view of how pain develops in endometriosis-associated pelvic pain. It undoubtedly interacts with other visceral pain conditions, probably in the bowel and the bladder. And I would encourage all of you here, as you’re expanding the horizon of reproductive medicine, to think about occasionally looking into the other fields in pain research, where there’s abundant growth going on.

[ASRM-Part 4 10.19.15.MP4 ends at 00:06:07]

[END RECORDING]